Eastern Timber Wolf (Ma’iingan)

The Eastern Timber wolf (Canis lupus lycaon), or Ma’iingan in Ojibwe, a subspecies of the gray wolf is currently the largest predator that inhabits the Leech Lake Reservation. It is also a species of cultural and spiritual importance to many tribal members of the Band. Once a common animal, it was extirpated from the reservation, as well as most of the rest of the continental United States by the early 1960s, due to unrestricted harvest by humans. Bounties were paid in Minnesota from the mid 1800s until 1965. The species received limited protection on Federal Land in 1966, but wasn’t fully protected until 1974 when it became one of the first species protected under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Under the Act, gray wolves were listed as endangered in Minnesota as well as the rest of the nation with the exception of Alaska. The Eastern Timber Wolf Recovery Plan, that was developed in 1978 under the ESA, listed the wolf as Threatened in Minnesota. Under protection of the ESA wolf numbers increased on the reservation and by the mid 1990s the wolf numbers on the Leech Lake Reservation had recovered and have been fairly stable since that time. The US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) has made several attempts to delist wolves from the ESA, but due to lawsuits and procedural issues it was not until January of 2012 that this occurred. Once delisting is secured management will revert back to Tribes and States so long as our management does not result in population declines and a need for relisting under the ESA.

IMPORTANCE OF WOLVES

Gray wolves have long been an important spirituality and cultural species to Native Americans. It is also a clan figure for some Native Americans. We were unable to find any historical information that would indicate that tribal members viewed wolves as a threat or that they harvested them to reduce their numbers. They did, however, take wolves for traditional and cultural purposes.

Many European cultures, on the other hand, feared and distained wolves and brought these beliefs to this country. Historically, in many cultures, large predators that compete, or are perceived to compete, with us for food, or are capable of killing us, have been persecuted and often their numbers have been greatly reduced or extirpated from the landscape. This perception continues to persist among some Minnesotans to this day, but due to research information collected over the years and educational efforts these perceptions are changing and wolves are tolerated by many people or accepted as a part of the ecosystem of the area.

WOLF SUBSPECIES

All wolves in North America are gray wolves (Canis lupus) but there are a number of subspecies. These include the Arctic Wolf (Canis lupis arctoss) that is found in north and northwest Canada as well as Alaska. The Plains or Buffalo Wolf (Canis Lupus nubiluss) that is found in the western U.S. The Eastern timber wolf, (Canis lupus lycaon) that is found in the northeast US and SE Canada. The Red Wolf (Canis lupis rufus) that is found in the Southeast US, and the Mexican wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) that is found in the Southwest US and Mexico. For a period of time there was uncertainty as to which sub species of wolves inhabited Minnesota, but the recent availability of genetic testing has found that the wolves that historically inhabited Minnesota were the Eastern Timber Wolf.

LIFE HISTORY

Gray wolves are one of the most studied predators in the world with extensive research conducted here in Minnesota. This research has helped to confirm or dispel many of the myths about wolves and their interactions with humans and their prey.

Size

The average male gray wolf in North America weighs about 80 pounds with females averaging about 10 pounds less. It is rare for a gray wolf to exceed 120 pounds. They typically stand 32-34 inches high at the shoulder.

Reproduction

Gray wolves breed in late winter and pups will be born in early summer in a secluded den site. Typically only the alpha male and female breed and the rest of the pack supports this litter of pups. The pups are born in late April or early May with an average litter size of 6-7. For the first couple of weeks the alpha female stays with the pups to keep them warm and fed. During this time she is totally dependent on the remainder of the pack to provide her with food. Once the pups are large enough to be alone the female can leave them and also hunt to support the growing pack.

Survival

Wolves have a difficult life and there are many sources of mortality. Under typical conditions about half the pups die before they reach six months of age usually due to shortage of food or diseases. There is also high mortality for older wolves with starvation, diseases, vehicle collisions, and illegal killing the most significant factors. In some populations over 50% of the adults are killed by other wolves as they try to defend their territories from other wolf packs.

Wolf Diseases

Gray wolf populations are known to contract a number of diseases and parasites including rabies, canine distemper, parvovirus, heartworm and sarcoptic mange. Some of these diseases can cause high mortality, especially in pups. In the past decade mange has also been reported in many of the wolves on the Reservation.

Prey

Gray wolves usually hunt in packs as it enables them to catch and kill large prey than they would typically handle on their own. They are most suited to catch medium to large ungulates, but will also feed on smaller prey items when available or out of necessity. In Northern Minnesota, and on the Leech Lake Reservation, this would have historically been Moose (Alces alces), Woodland Caribou (Rangifer tarandus), Plains Bison (Bison bison), Eastern Elk (Cervus canadensis canadiensis). Due to timber harvest that altered the composition of our forests and overharvest by European settlers all of these species have all been extirpated, or in the case of the Eastern Elk, it is extinct. The forest found here now are more suitable for white-tailed deer and this is the primary prey species for wolves on the Leech Lake Reservation. The other common food item in their diet here is beaver that have also prospered from the conversion of pine and hardwood forests to young aspen.

Under most circumstances wolves have a difficult time catching and killing a healthy mature animal. For this reason much of the prey they eat are either very young animals, injured, or old individuals of a population. In many respects this helps to keep the prey population “healthy” by removing the individuals that are not as strong, smart, or healthy as other individuals of their species. Despite the perception that a pack of wolves have an easy time catching food they are frequently unsuccessful and may go for long periods without food. It is also risky to corner an ungulate as a single well placed kick can kill or seriously injure a wolf. Once a prey animal has been successfully killed the entire pack will feed on the animal with the more dominate animals eating first.

Wolf Packs

A wolf pack is made up of the Alpha Male and Female and a few other members, usually the offspring from the past year or two that have not dispersed yet, as well as any surviving pups from the current year. Pack size varies primarily dependant on the size of the prey species they hunt. Here in Minnesota, where white-tailed deer are the primary prey the average spring pack size, based on four studies, is 5.3 animals. In areas where larger tough prey, like moose, bison, or muskox, are hunted packs will usually be larger. Larger prey items also means that each kill can feed more pack members.

Contrary to popular belief the number of wolves in a particular area does not just keep increasing. It is limited by the amount of food and further restricted by adjacent packs. Here in Minnesota the average size pack in mid winter is 5.3 animals. Once a pack exceeds this number, members of the pack, typically yearlings or any remaining two year olds will start to disperse in an attempt to find a mate in an unoccupied territory where they will try to establish a new pack. This is a very dangerous time for wolves as they will have to cross other pack territories, encounter roads, humans, and unfamiliar area where prey patterns are unknown. These dispersing wolves are the ones that have recolonized Wisconsin, Michigan, and other parts of the upper Midwest. Although, a pack territory may be occupied for many years there are occasions when an area may become unoccupied. The loss of the alpha male or female, for example, might cause a pack to disband. Strife between adjacent packs might also result in the killing of enough members of one pack to cause the remainder of members to abandon a territory.

Territory Size and Wolf Numbers

In Minnesota wolf territory can be any where from 42 miles square (6.5 miles x 6.5 miles) to 100 square (10 miles x 10 miles), but territories as large as 200 square miles have been reported. Excluding large bodies of water and unsuitable habitat the Leech Lake Reservation can provide habitat for upwards of a dozen wolf packs, some of which have territories that extend outside the reservation. At 5.3 individual wolves per pack this means that there are about 60 wolves on the reservation. Wolves tend to spent much of their time in the core of their territory and lesser amounts on the fringe where they are likely to have dangerous encounters with adjacent packs.

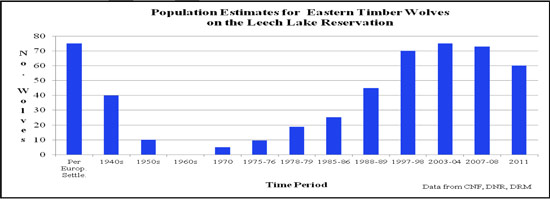

The graph in Figure 1 outlines the general trend of the wolf population on the reservation over time. Wolf numbers started to drop shortly after the arrival of Europeans and by the 1960s and into the 1970s they were all but absent from the reservation. This was due to changes in habitat due to timber harvest that altered the prey base and unregulated killing. Since protected under the ESA their numbers have increased and they are currently fairly stable at numbers thought to be similar to pre European Settlement.

Figure 1. Estimated wolf population trend on the Leech Lake Reservation:

HUMAN CONCERNS ABOUT WOLVES

Concerns about wolves is usually confined to four areas. The first is predation on commercial livestock, the second is affect on wild ungulate populations, the third is pet safety, and the fourth is human safety.

Livestock

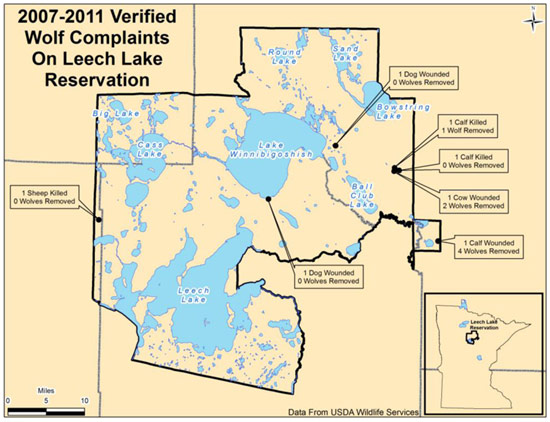

On the Leech Lake Reservation there is almost no commercial livestock production so this is of minimal concern. Over the years there have been very few wolf damage complaints from within the boundaries of the Leech Lake Reservation. Figure 3 outlines the locations of wolf complaints over the past five years. The USDA Wildlife Services is set up to deal with wolves that kill livestock and the MN Department of Agriculture has paid for lost animals. This system has worked well for many years and it is hoped that some version of it will be maintained into the future.

Figure 3. Locations of wolf complaints from 2007-2011 on the Leech Lake Reservation:

Whitetailed deer

Wolves do eat deer on the Leech Lake Reservation, but their affects on the overall population is minimal. To a large degree wolves take young, injured, and old animals that naturally would have high mortality anyway. In the grand scheme of things there is little difference in how an individual in a population dies; it is just cycled through the food web in different ways. Here in Minnesota, available information strongly suggests that at current wolf populations they do not suppress white-tailed deer numbers. Even after the severe winters of 1995-1996 and again in 1996-1997, when upwards of half the deer died in the wolf range, and wolf numbers were high, the MN DNR found that the deer population recovered much faster than anticipated by regulating human harvest only. Despite having wolf numbers at or near saturation levels for several decades in northern Minnesota it has been possible to maintain high deer numbers. In many cases efforts are underway to try to reduce deer numbers to provide for other interests and concerns.

The biggest factors affecting deer populations on the reservation is the severity of the weather, and the level of human harvest. With our winters becoming warmer there are fewer and fewer years when winter severity is killing many deer.

Human harvest is currently the largest factor controlling deer numbers. This harvest is regulated and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources (DNR), who regulate State licensed hunters and the Leech Lake Band’s Division of Resources Management (DRM) who regulate tribal hunters. By working together we strive to balance the desires of deer hunters with the need to keep deer populations low enough so they do not reduce habitat for other wildlife or other interests like forest regeneration, or medicinal plants. It was not all that many years ago that deer numbers had increased to such high levels that they were concerns over vehicle collisions, damage to forest habitats, and reductions or loss of some plant and animal species.

This is not to say that wolves do not reduce deer numbers in localized areas. In the core of a wolf pack’s territory deer soon become wary and tend to be move to the outer edges of the wolf territory. If your favorite hunting spot is in the center of a pack territory you may see fewer deer, but just as hunters move their hunting spots as trees mature and the habitat changes that reduces deer numbers, a move due to wolves can also be beneficial. If people are willing to move into wolf pack fringe areas they have an increased chance of seeing more deer as they will be concentrated there.

Pet Safety

Pet safety is also of concern in some area as wolves on occasion will kill or injure pets, especially if they are allowed to run free. This issue is also of minimal concern on the reservation with only two injured dog reports occurring in the past 5 years (Figure 3).

Human Safety

Human safety is occasionally of concern even though wolf attacks are very rare and one has never been reported on the Reservation. Of the cases reported elsewhere rabies or a wolf that has become habituated to humans is often a contributing factor. Much of the fear of wolf is rooted in European history and folklore from the Dark Ages. During this period the black plague killed large numbers of people and apparently European wolves sometimes scavenged on bodies that were not disposed of properly. There is little reason to fear wolf attacks on humans on the Leech Lake Reservation. Wolves can sometime be quite curious, and will occasionally investigate human activity, but will generally run at the first sign of humans

MONITORING

The Leech Lake Reservation encompasses approximately 800,000 acres of land and water, but the amount of land under tribal title is only about 30,000 acres. For this reason it would be impractical to only conduct monitoring on our lands, and there are some wolf packs that occupy territories that are both in and outside the reservation boundaries. This is the reason we participate in the multiagency monitoring program that has been conducted across much of northern Minnesota approximately every five years. This gives us a much better picture of the wolf population on the reservation. It is the plan of the DRM to continue to support and participate in these monitoring efforts into the future. The band will also work with the DNR to establish harvest quotas should either party decide to allow for such harvest.

RESOURCES USED IN PREPARATION.

Ballenberghe, V. V. 2011. Intensive Management-or Mismanagement? Wildlife Professional. 5: 74-77

Berg. W. E. 1986. Gray Wolf Occurrence on the Chippewa National Forest 1985-1986. Special Report to the Staff of the Chippewa National Forest

Erb, J. S. 2012 Personal Communication. MN DNR Erb. J. S. Benson. 200??. Distribution and Abundance of Wolves in Minnesota, 2003-04. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Report.

Fritts, S. H. 1982. Wolf depredation on livestock in Minnesota

Fuller, T. K. 1997.Guidelines for Gray Wolf Management in the Northern Great Lakes Region. Dept. of Forestry and Wildlife Management, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA. Technical Publication 271.

Hazard, E. B. 1982. The Mammals of Minnesota. University of Minnesota Press

Lopez. B. H. 1978. Of Wolves and Man. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York.

McNay, M. E. 2002. A Case History of Wolf-Human Encounters in Alaska and Canada. Alaska Department of Fish and Game Wildlife technical Bulletin 13.

Mech. L. D. 1970. The Wolf. University of Minnesota Press

MN Department of Natural Resources. 2001. Minnesota Wolf Management Plan.

Nature Serve. 2012. Canis lupus. http://www.natureserve.org

Red Lake Department of Natural Resources. 2010. Red Lake Band of Chippewa Indians Gray Wolf Management Plan.

Stark, Dan. 2012. Personnel Communication

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 1992. Recovery plan for the Eastern Timber Wolf. Twin Cities Minn. 73 pp.

Contact Us

DRM (218) 335-7400

| Name | Title | Phone |

| Mortensen, Steve | Fish, Wildlife & Plant Resources Program Director | 335-7421 |

| Finn, Jon | Fish & Wildlife Field Specialist | 335-7424 |

| White, Gary | Assistant Hatchery Manager | 335-7424 |

| Robinson, Martin | Fish and Wildlife Technician | 335-7424 |

Division of Resource Management

Division of Resource Management